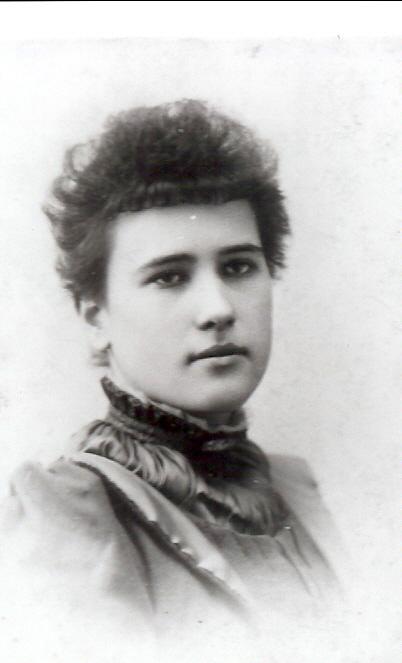

Elizabeth "Bess" Maddern

before marriage.

Elizabeth Maddern, who preferred to be called Bess, was born in 1876, and grew up in Oakland, where her father was a plumber. In the mid-1890s she met Jack through his acquaintance with her brother Ted. In hope of earning enough money to go to the University of California, Bess, a natural teacher, gave tutoring lessons in grammar and algebra. When Jack decided to apply for the university, Bess tutored him in the mathematics he would need for the entrance exam. With other California women of her generation she was athletic and challenged convention by wearing bloomers when out hiking or bicycle riding. Although these adventurous qualities were ones Jack admired, he was not attracted to Bess. She eventually became engaged to another friend of Jack's, Fred Jacobs. Meanwhile, while Jack fell in love with a fragile blond woman of English parentage, Mabel Applegarth, a relation he fictionalized in his novel Martin Eden.

Both love ties were broken: Bess's when Fred died on his way to fight in the Spanish-American War, and Jack's when he realized that Mabel was not suited to his intellectual ways. Jack then developed an interest in fellow socialist Anna Strunsky, He even proposed they write a book together in which each would take the role of a position on love: hers the romantic, and his the objectivist. Anna was Jack's intellectual match, but she was also Jewish, and his beliefs in Anglo-Saxon superiority may have unconsciously prevented him from pursuing marriage. While Anna believed she was the only woman in his life, he was also keeping company with the grieving Bess, whom he found a good sport on their many outdoors adventures.

In April of 1900 Jack shocked his friends and family by marrying Bess. He said the marriage was based not on love but on science, a position he espoused in The Kempton-Wace Letters, that it would provide a steady foundation for a writing career. Bess presumably agreed with this position, although it was soon clear that she was in love with him. The precipitate marriage was not advantaged by the couple's inclusion of Jack's mother and nephew into the household. Nonetheless, the two managed well enough in the early months, and Bess was soon pregnant. They would eventually move to an idyllic spot in the Piedmont hills. (Jack describes this well in his story "The Golden Poppy.")

The household became a focal meeting ground for The Crowd, a collection of Bay area Bohemians. Bess's life centered on home management and helping Jack by typing and editing his manuscripts. With more free time, Jack did not give up his pre-marital ventures with friends, and worse, realized he was still in love with Anna Strunsky, who came to the house to work on their collaborative book. With Bess pregnant a second time, Jack took off to England, and Anna broke of their relationship. Upon his return, letters to friends show he decided to rebuild the marriage and did so. He discussed moving the family away to Southern California.

The summer of 1903 brought events that ended the marriage for good. Jack fell in love with old friend Charmian Kittredge and deserted Bess and their two daughters. The divorce granted in 1905 was not congenial. The aggrieved Bess would never allow the girls to visit Jack in the presence of Charmian. He in turn complained about her attitude and both argued over money. Each contributed to the ongoing rancor to the time of Jack's death in 1916. When Bess became engaged to Charles Miller, Jack's influence impelled her to cancel the marriage. Jack's will left Bess virtually nothing and even named second wife Charmian as his daughter's guardian.

Despite the arguments with Jack, Bess created a satisfying life, both devoted to her daughters and her growing business as a tutor. By middle age, though, serious heart disease developed. During her later years, Bess enjoyed travelling when she could and caring for her grandchildren. In 1938 a profound stroke left her almost completely bedridden, so paralyzed she was unable to speak. She would remain that way until her death ten years later. The brief obituary referred to her as Jack London's widow.

Bess Maddern's role in Jack London's life has been colored by his post-divorce correspondence, which is full of vitriol toward her. Less than a dozen letters to anyone in her own hand remain, and most of these are her angry letters back to him. What she really thought and how she actually behaved during their marriage is thus difficult to ken. It is not surprising that some writers have described her in very negative terms. Whether she was shallow, sexually cold, and such, as London claimed, cannot be corroborated. She kept silent, and thus leaves her life as she saw it virtually closed to the historian's gaze.

Sources

Labor, Earle, Robert C. Leitz III, and I. Milo Shepard, The Letters of Jack London, 3 volumes, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988.

Joan London, Jack London and His Daughters. Berkeley, CA: Heywood Books, 1990.

Andrew Sinclair, Jack: A Biography of Jack London. New York: Harper & Row, 1977.

Clarice Stasz, American Dreamers: Charmian and Jack London. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1988.

______.Jack London's Women. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003.

Travernier-Courbin, Jacqueline, "Bessie: The First Mrs. Jack London." Jack London Journal, no. 5 (1988): 168-218.