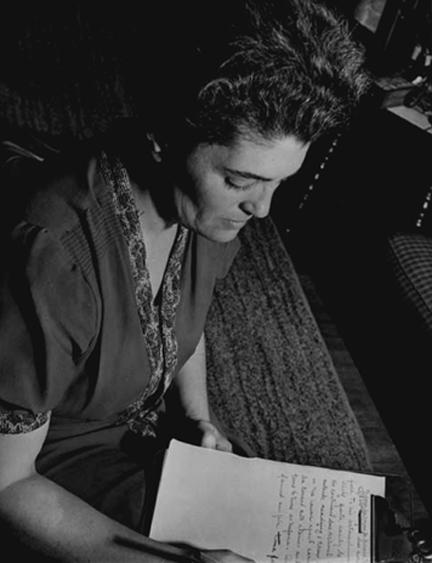

Joan London

Joan London was born to Jack and Bess Maddern London on January 15, 1901. Her father was so smitten that he kept a special photo album to memorialize her importance for him. Unfortunately, he would leave her daily presence when she was only two and a half. She and her younger sister Becky lived with their mother, who was assisted by Jenny Prentiss. They looked forward to their fathers visits, which often had large gaps while he traveled, such as during the 1907-09 Snark voyage. He inculcated the girls with a sense of courage, physical agility, and love of literature. Less conventional than their mother, Jack brought his own sense of play, which often included challenges to build the girls' confidence.

Bess Maddern was a devoted mother, who saw that her girls were always well-dressed and exposed to many opportunities through travel and the arts. The girls also had pets and a garden with chickens in the backyard. Bess often pressured Jack for extra money and resources, and ensured that he provide a new home in the Piedmont hills overlooking the Bay area.

At age 5, Joan began to write letters to her father and inform him of her activities with her sister. She sought his approval through her own attempts at writing. In 1911, a bout with diphtheria brought him often to her bedside, and he tried to get Bess without success to allow the girls to visit the Beauty Ranch. This disagreement continued to his death, and Joan was often caught in the middle by having to make requests in place of her mother doing so directly. In 1914, following the destruction of Wolf House, Jack became so upset with her that he wrote a nasty letter in which he essentially cut her off emotionally as his daughter. Calling her a "ruined colt," he said he would not recognize her were he to pass her on the street. Joan continued to write to him anyway, and Jack eventually came around. Nonetheless, he missed her high school graduation in 1916, just as he had missed many of his daughters' various dramatic and dance performances.

Joan shared many of her father's qualities: a sharp intellect, disciplined work habits, support for the underdog, and expressive emotions. In high school she edited the school literary magazine and was a leader in several clubs. She had just entered the University of California at Berkeley when her father died. There she most enjoyed history and developed sophisticated approach to research.

After graduating Phi Beta Kappa, she married Park Abbott, and had a son, Bart. Though the marriage lasted only three years, the couple shared custody of the boy and remained close friends to their final days. In 1925, Joan started a career as a lecturer, speaking at clubs around the country on such themes as feminism, political issues, and her father. She befriended Charmian London, who served as a mentor for the next decade. She was less successful in her freelance writing career, her most notable project being the serial novel Sylvia Coventry, a love story in the context of farm labor exploitation in Hawaii.

of "The Call of the Wild."

Joan's second husband was Russian specialist Charles Malamuth. Despite problems in the marriage, she joined him in Moscow in 1930, where her strong personality impressed e. e. cummings to feature her in his book EIMI. Joan divorced Malamuth in 1934 and moved to Hollywood, where she ran a secretarial service and assisted other writers. Her friends were primarily film people who were immigrants from Central Europe, and thus of radical political persuasion. (Photo shows son Bart and her with Clark Gable on the set of The Call of the Wild.)

Joan returned to San Francisco in 1936, during a time of major labor unrest. She worked for the maritime union and corresponded with Leon Trotsky and socialists who had known her father. With Barney Mayes, who may have been her husband, she wrote pseudonymous crime story, Corpse With Knee Action, based upon violence on the San Francisco waterfront. They also wrote an unpublished book, Embarcadero. She also published a biography of her father with emphasis upon his socialist development and ideas. Her skill as a historian and writer came to fruition in this lively account of Jack London's times.

After leaving Mayes, Joan became the publications editor and research librarian for the California Labor Federation. She created the library, wrote speeches and newsletter articles, and provided lawyers with background material. Aligned with Trotskyism, she became under the surveillance of the FBI during the late 1940s. Even Joan's new husband, stonemason Charles Miller, came under the FBI despite his apolitical stance. As a result of the spying, Joan quit her activism in order to save the state labor contingent from being tarnished.

After her retirement, in the 1960s Joan was once more an activist, specifically with the Citizens for Farm Labor, Women Against War, and related activist groups. This brought her again under political scrutiny, this time of the California Senate Subcommittee on Un-American Activities, which condemned her work in the farm labor movement, and her teaching college students protest and strike techniques.

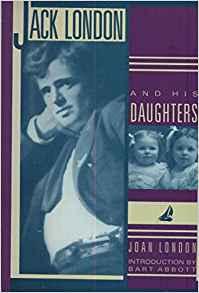

With fellow activist Henry Anderson, Joan wrote a history of the farm movement in California, So Shall Ye Reap. For this and other efforts, she received the Award of Merit from the American Association for State and Local History. She began two others books, one a biography of her purported grandfather, William Chaney, and one on the consequences of growing up under two parents who constantly disputed following their divorce. Joan blamed both Jack and Bess for the unhappy aspects of her childhood, and did not want others who divorced to repeat that pattern. In late 1970, both Park Abbott and Charlie Miller died. Joan had long been suffering from cancer of the throat, and died in January, 1971. She extracted a promise from son Bart to see that her manuscript on her childhood be published, which he did, Jack London and His Daughters.

Joan London was the public sister, similar to her father a large personality, brilliant, impatient, and committed to her causes. Where Charmian London continued Jack's literary legacy, Joan kept his political beliefs in the forefront. She seemed always in her father's shadow, determined to please him, long after his passing. Her private life, afflicted at times by drinking, could be chaotic. Apart from her son, her causes came first. On February 8, 1971, California the State Senate unanimously passed a resolution in recognition of her work "as a warrior for labor with a passion for economic justice from early adulthood until the end of her life."

--Clarice Stasz

Sources

Labor, Earle, Robert C. Leitz III, and I. Milo Shepard, The Letters of Jack London, 3 volumes, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988.

London, Joan. Jack London and His Daughters. Berkeley: Heyday Books, 1990.

Sinclair, Amdrew.Jack: A Biography of Jack London. New York: Harper & Row, 1977.

Stasz, Clarice American Dreamers: Charmian and Jack London. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1988.

______.Jack London's Women. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003.