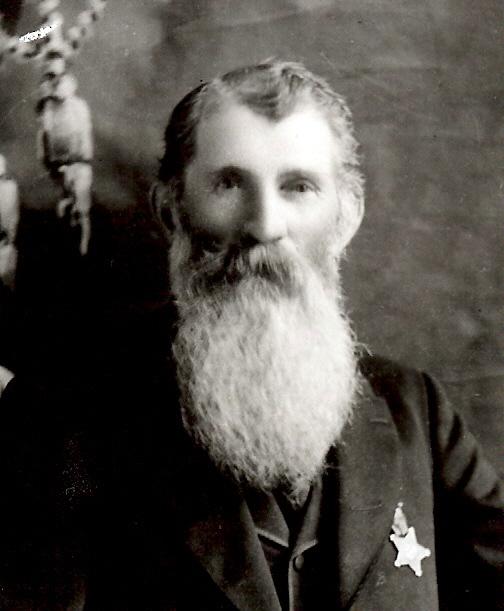

John London

John London was born on January 11,1828 in Clearfield County, Pennsylvania. He worked on the family farm until adulthood, then joined a railroad gang. He must have had special talent and knowledge, because in short time he was made crew boss. Clearly, he enjoyed rural life, for after marriage to Anna Jane Cavett, he farmed in Wisconsin, Illinois, and Missouri. His family grew steadily, for Anna Jane gave birth eleven times over twenty years. At age 36, he left his family to join the 126th Illinois Volunteers, and fought in battles in Arkansas. Like so many Civil War participants, illness brought disabilities. Measles and repeated bouts of pneumonia left him with only one functioning lung.

After being honorably discharged for his disability, he took his family to Iowa, where he supervised the building of a bridge over the Cedar River. After that, the family lived in a prairie schooner for several years before settling a homestead outside of Moscow, Iowa. There John learned the language of the local Pawnees, hunted for meat, tilled the soil, and sustained his family in that harsh environment. These behaviors hint at a man prepared to do what is necessary, and willing to work hard. But the family life shattered in 1873, when Anna Jane died of consumption, leaving John with two small daughters, Eliza and Ida, and a son.

A family without a mother could not survive on the prairie, so John London moved to California. His son soon died, and he placed his daughters in an orphanage while he tried various jobs in San Francisco, such as door-to-door sales. A man without prejudice, he befriended the Prentiss family, who introduced him to Flora Wellman. He was fifteen years her senior, but very different from the blustery William Chaney Flora's previous partner. The few remembrances of John London that survive refer to his kindness, and his sympathy for the underdog. Such may explain his attraction to Flora, abandoned with an infant son. Flora was also well-equipped to run a household that would include two other small children. They married on February 19, 1877, and by all accounts had a convivial relationship throughout the years.

Eliza and Ida Shepard soon joined the family, as did at some point later little Johnny, as he was known. There followed years of difficulty for John London as a wage earner. He did not have the stamina for high-paying construction work, nor did he have the education for a profession. Consequently, he tried various ventures, including a store in Oakland, a small farm in Alameda, a ranch in San Mateo, a farm in Livermore, a boarding house in Oakland, and various odd jobs. The repeated failures were sometimes outside his control, as when his large flock of chickens died of a virus. But he and Flora were also tempted by gambling, and that stole some of the household money. Perhaps it was gambling that provided the money to invest in their various ventures. Despite the constant moving and economic failures, the family lived as respectable working class of the day. The children completed grade school, the highest education most youth achieved then, and unlike the real poor, the household had a piano, linens, vegetables and steak on the table. Flora worked alongside John, as well as gave piano lessons, mended clothes, and baked bread.

Johnny believed that John London was his natural father, that Eliza and Ida were his real sisters. John London taught the boy to sail on the Oakland estuary, to fish for rock cod, and to shoot ducks and coots. He also took his son to local waterfront bars, where he learned of the life at sea and the possible adventures it promised. John was also a raconteur, able to spin wonderful stories, another skill his son absorbed and expanded upon.

In adolescence, Johnny changed his name to Jack, and set out on his own adventures, on a sealing ship, hoboing on the rails, and in factories. John was eventually able to collect a veteran's disability pension, and work as a watchman on the waterfront. In 1897, several months before leaving for the Yukon, Jack learned the truth of his paternity. He took his spite out on his mother, and continued to honor John London, the man who raised him, as his real father. John London died that fall at age 69, but his stepson, snowbound in a Yukon cabin, would not get the news until the following spring.

Like many Civil War veterans, John London found disability prevented him from providing an affluent lifestyle to his family. Nonetheless, he remained faithful to his role, and offered stepson Jack a model of kindness and stability. John London's descendants in the Shepard family have asserted he was Jack's biological father. Although the truth of paternity will never be known, that he was Jack's real father in terms of love and support is indisputable.

--Clarice Stasz

Sources

Atheron, Frank Irving. "Jack London in Boyhood Adventures." Jack London Journal, 4 (1997): 14-172.

Kingman, Russ. A Pictorial Biography of Jack London. New York: Crown, 1979.

Stasz, Clarice. American Dreamers: Charmian and Jack London. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1988.

Walker, Franklin. Notes for unpublished biography of Jack London. Franklin Dickerson Walker Collection, Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino, CA.