William Chaney

William Chaney was a man of the 1800s: one of many men always on the move, but more as an explorer of ideas rather than of new economic opportunities. He was born in a log cabin in Chesterville, Maine on January 13, 1821. He came from a family line of early settlers, farmers like his father, who owned 1500 acres. When he was nine, his father died, and with his young sisters he was bound out, essentially sold as labor to another farmer. At sixteen he escaped to the sea, but found the life lacking. He wandered around various mid-Western states, and by 1846 was admitted to practice law in Virginia. Several years later he was a lawyer and city clerk in Iowa, and married an unknown woman who died of cholera soon after. He returned to Maine, where he ran a small newspaper and married Mary Jordan. He became head of the Maine Know-Nothing party, and its anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant mission. His marriage lasted but a few years, and his wife divorced him.

Chaney's life took a major shift in 1859, when he moved to Boston and became editor of The Spiritualist Age, the leading publication of Spiritualism. Long a critic of seances and occult practices, Chaney attended events that changed his views. He left the editorship because the journal also supported abolitionism, yet he remained a spiritualist to the end of his life. In Boston he lived on lecturing, free-lance writing, and editorial work. He claimed to write three books then: The Mertons, The Mission of Charity, and Minnie the Medium, or Spiritualism in Germany.

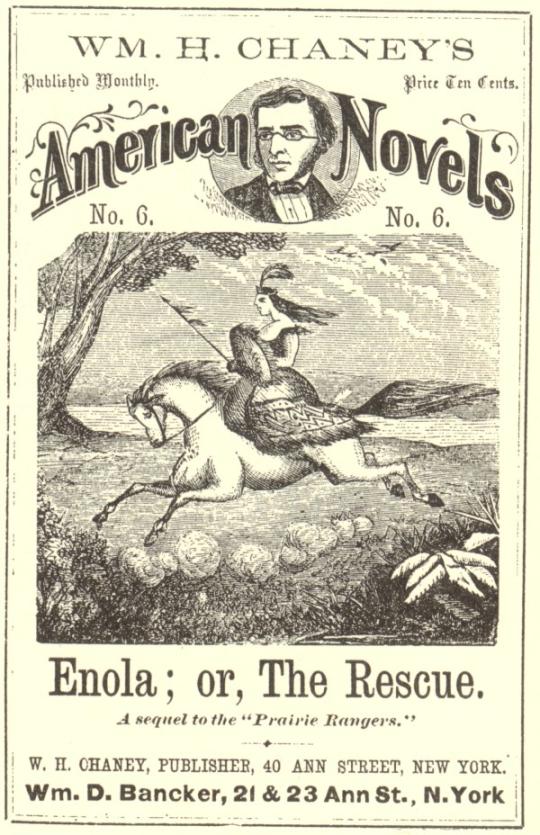

At the end of the Civil War, Chaney moved to New York City. There he became involved in the seamy world of cheap printing, publishing, and advertising. This activity included the reprinting of others' works, sometimes under his own name. His mailing address was the location of a printing house, advertiser for cheap watches, and various medical nostrums. Whether he was involved in the mail order sales is unclear. This was the time of nickel and dime novels, books his future son would look to for entertainment.

Chaney's life became somewhat more settled in 1866 when he befriended Luke Broughton, an immigrant British doctor who had come to the United States to popularize astrology. It was Chaney who would accomplish that task. He believed astrology "the most precious science ever made known to man." Knowing a child's horoscope, he explained, could help one "develop all that is good" in the child's character. He incorporated in his astrology the ideas of Herbert Spencer, with his notions of the inherent superiority of Anglo-Saxons. In 1867, Chaney was jailed in New York's Ludlow Street Jail for disrupting a religious ceremony and assault. After six months he was freed with no charges made. He may have had another short-lived marriage in New York.

ln 1870, Chaney moved to the Northwest. He was involved in futile plans to open a college of spirituality in Oregon, and challenged ministers in Olympia, Washington Territory to debate him on the historical sources of the Bible. He claimed to have met Flora Wellman in Seattle, where she was staying in a boarding house. She was a Spiritualist, so it makes sense they would cross paths. In 1873, the Daily Alta California noted the arrival in San Francisco of one “Miss Flora Wellman, [from] Springfield, Ohio”)later. Chaney arrived a year Whether they actually married, as he claimed, will always be unknown because the reputed place of marriage, San Francisco, lost its civic records in the great fire of 1906. On the other hand, in an 1874 news article, he referred to "Mrs. Chaney" being active with him in sprirtualist pursuits. At that Western port city the couple became part of a group that published Common Sense: A Journal of Live Ideas. They were "pro-labor, pro-Negro, pro-Grange," and against organized religion. Chaney published essays in that magazine, and became a noted lecturer on such topics as prison reform, the Bible as fiction, and a strong defender of of astrology.

When Flora became pregnant in 1875, newspapers reported that he abandoned her when she refused an abortion. Although he stayed in San Francisco, he never saw his newborn son. Although most evidence points to his fathering Jack London, and Flora even gave birth as "Mrs. Chaney," the truth will never be known for certain. Jack grew up believing John London was his real father. When he learned the truth at age 21, he contacted Chaney, who denied being the biological father. He accused Flora of having other lovers at the time of Jack London's conception, and claimed he was himself sterile. Yet during his time in San Francisco, Chaney cut himself off from the spirtualists aligned with free-love advocate Victoria Woodhull. So either he lied to the newspapers when he was living with Flora, or he lied to Jack.

Chaney moved to Salem, Oregon to reestablish his law practice and write for spiritualist publicaations.Chaney prepared and published an ephemeris, the reference required for calculating horoscopes, as well as lectured and trained students. He was thus responsible for introducing rigor into what had been a haphazard approach to astrology in the United States before his proselytizing. He was also involved in mining interests and a railroad incorporation, perhaps as a lawyer. He married Fidelia Eddy in 1880, who divorced him in 1889 after he had deserted her to live in New Orleans and St. Louis.

Chaney's later life was spent in Chicago.. Poor out of choice, he invested his income into his astrological .publications. In 1900, fellow astrologers praised him, and observed how at age 80 he was still working every moment. He also continued to deride religion, particularly Christianity. He continued to claim Adam and Eve no more existed than Santa Claus. Chaney died in Chicago on January 8, 1903. Several months prior, while in good health, he had predicted his death, thus designed his own funeral plans. He was buried in Elmwood Cemetery during a snow storm, his friends in purple regalia as requested. His estate included 800 books. Because only twenty-five years of grave maintenance were paid, years later his body was disinterred, and placed in some unmarked spot to make room for another.

Decades later, his purported granddaughter, Joan London, did extensive research toward a biography of Chaney, but she died before she could complete the manuscript. Part of her motivation was to correct the biographers who portrayed him as feckless and irresponsible, when in fact he had lived during a time of great mobility. A well-trained historian, Joan noted to a friend that Chaney was "like many Americans of his time, who sought more favorable environments for their hopes and ambitions,...when the frontier was moving to the west and southwest." He might have had an element of charlatan within him, she concluded, but he was "in that mainstream of nineteenth-century idealism best recognized today by the names of his three contemporaries: Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman." Her reappraisal went too far, perhaps, but her intention was to defend her father's reputation, to correct the view that he was the bastard son of a ne'er-do-well crank.

--Clarice Stasz

Sources

Burby, Tom. William Henry Chaney: The Strange Journey of Jack London's Father. [Accessed 2019 at https://www.strangenewengland.com/2015/07/20/william-henry-chaney-the-strange-journey-of-jack-londons-father/, no longer an active link]

Chaney, William. Primer of Astrology and American Urantia. St. Louis: Magic Circle Publishing Company, 1890.

Demerast, Marc. "The Flinty-Headed Calculator: Some Notes on W. H. Chaney (1821-1903)"

London, Joan. "W. H. Chaney: A Reappraisal." American Book Collector, (November, 1966): 11-13. Notes on her planned biography are in The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

Mood,Fulmer, "An Astrology from Down East," New England Quarterly, 5 (1932): 769-99. [Joan London helped Mood prepare this article.]